Credit markets update:

History’s warning on political influence of the Fed

Fears of White House retaliation tilted policy toward short-term growth at the cost of higher inflation in the 1960s and 1970s.

This credit report examines how political pressure shaped Federal Reserve policy during the Great Inflation and what that means for markets today. Drawing on FOMC (Federal Open Market Committee) transcripts from the 1960s and 1970s, it shows how fears of White House retaliation and Congressional demands repeatedly tilted policy toward short-term growth at the cost of higher inflation. With today’s far more open and integrated capital markets, a politically compromised Fed would likely face a sharper, faster market reaction. Rising term premiums and a softer dollar already hint at how quickly confidence could erode if the Administration were seen to be exerting greater control over the Fed.

Eroding institutional independence

A few weeks ago I highlighted the risk to long-term interest rates as markets grow more wary of the institutional changes emerging in the US under President Donald Trump. At the heart of these changes is an attempt to concentrate power in the executive branch. In line with the Heritage Foundation’s Project 2025 report, Trump seeks to expand presidential control over functions traditionally divided among independent agencies, Congress, the judiciary and other institutions. While framed as a drive for more efficient policy execution, this marks a clear break from how US institutions have traditionally been built and from the norms of other liberal democracies.

Among several examples, two stand out. The dismissal of former BLS chief Erika McEntarfer raises concerns that statistical agencies could become agents of the administration rather than independent providers of data. More striking still are Trump’s repeated attacks on, and pressure applied to, the Federal Reserve, most recently his failed attempt to dismiss Governor Lisa Cook.

Central bank independence sits at the core of these developments. Politicians typically operate on four-year election cycles, whereas central bankers are granted longer terms and operational autonomy to focus on the longer-term consequences of policy actions. This ability to take a longer view is crucial: in 2003, Walsh reviewed studies showing that more independent central banks achieve lower inflation without any increase in output volatility.

Central-bank independence is treated by most investors as an undisputable feature of the policy landscape rather than a variable. Because few have ever seen a developed-economy central bank under overt political control, there is little intuition about what that would mean. This lack of experience creates a blind spot: it is easy to call undermining the Fed’s independence “bad for markets,” but far harder to picture the concrete channels through which policy, inflation and financial-market behaviour would actually change.

"Great Inflation" period

This report aims to help fill that gap. It draws on research using transcripts and minutes from the 1965–1984 “Great Inflation” period, when members of the Board of Governors repeatedly spoke about aligning policy with administration wishes. It shows how a non-independent central bank operates, how it reasons under political pressure, and what the economic and inflationary consequences can be. This historical perspective should make it easier for investors to gauge today’s risks if similar pressures were applied to the Fed under modern conditions.

The intellectual framework of the 1960s

Before examining how the central bank was influenced by government, it is important to step back and understand the context in which policymakers operated. In his March/April 2005 remarks published in the Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis Review, Alan Greenspan traced the evolution of US macroeconomic thinking from the Keynesian revolution of the 1930s to the post-war policy consensus.

- By the 1960s, many economists and policymakers believed that active regulation, state intervention and demand management, including central-bank action, could improve on earlier efforts to achieve and maintain full employment.

- Short-run objectives shifted toward running a “high-pressure” economy on the assumption that any inflationary costs would be modest and tolerable relative to employment gains.

- Moreover, they believed that incomes policies, wage and price controls, and “jawboning” could contain price rises at little macroeconomic cost.

Greenspan argued that this approach, grounded in the Keynesian framework, ultimately ran into the “ugly reality” of stagflation by the 1970s, prompting a fundamental reassessment of policy. And in this environment, the Fed itself was not acting in a vacuum; instead, growing political and institutional pressures shaped its decisions.

Evidence from the 1960s

On its face, the historical backdrop does not imply that the central bank was less independent. Yet, Allan H. Meltzer’s work shows that compromised independence was not just one of many contributing factors but, in his view, the key source of the persistent high inflation from the mid-1960s to the end of the 1970s.

In his paper “Origins of the Great Inflation”, Meltzer argues that the policy errors of the 1960s and 1970s arose from several interlocking factors. He highlights three in particular:

- Leadership style. Chairman William Martin’s insistence on consensus within the FOMC delayed prompt anti-inflationary action and allowed inflation to gain momentum.

- Flawed analytical frameworks. Policymakers downplayed the monetary roots of inflation, treating price rises as transitory and not requiring forceful responses.

- Compromised independence. Institutional arrangements that promoted fiscal–monetary coordination undermined the Fed’s autonomy. Meltzer contends that this political influence, internalised by both Martin (who was the head of the Board of Governors until 1970) and Arthur Burns (who took over after Martin in 1970), was arguably the most significant factor preventing timely and effective disinflation.

These themes are visible in the FOMC’s own discussions. A clear early example comes from December 1965, when the Committee debated whether to tighten policy as inflation began to rise.

In this discussion, members openly debated how to adjust policy without colliding with the Administration. Chairman Martin wanted to raise interest rates but, fearing for the System’s independence if it acted against the President’s wishes, hesitated: ‘There is a question whether the Federal Reserve is to be run by the administration in office.’

This is in itself a remarkable statement: Should the Fed act in a way that wasn’t in the interest of the administration, Martin feared that the Fed would be taken over by the administration. This fear made it more difficult for him to act in a way he believed to be right (by raising interest rates).

Other members also had reservations against tightening the monetary policy stance. Three out of seven members voted against: Robertson, Mitchell and Maisel.

Robertson argued that inflation was not inevitable and warned that higher rates might trigger a recession and raise Treasury borrowing costs. Mitchell opposed an increase on political grounds, noting that the Fed “appeared to be on a collision course with the administration” and preferring to negotiate with the Administration on how to raise rates. Maisel’s main concern was the recovery, but he also believed they should wait for the President’s budget in mid-January before adjusting rates. He favoured incomes policy to control prices and wages: “A discount rate increase ... could be interpreted only as a vote of no-confidence by this Board in the national goal of growth at full employment.” If inflation rose, he argued, the Board could act later.

When the Fed implemented higher interest rates, it accompanied the move with a statement saying it had “no intention of imposing a severe ‘tight money’ policy that would render bank loans difficult to get.”

President Johnson criticised the decision publicly, saying it would hurt consumers and state and local governments and complaining that “the decision on interest rates should be a coordinated policy decision in January.” Interestingly, the New York Times editorial supported the President on coordination while recognising that inflationary pressures had increased.

This exchange shows how concerns about co-ordinating with the White House, protecting Treasury borrowing costs and maintaining “full employment” shaped the Board’s willingness to act on inflation, exactly the dynamic Meltzer identified.

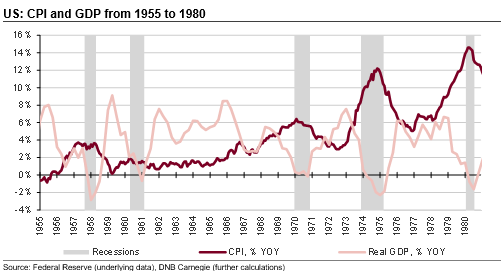

The desire to coordinate with the administration continued throughout the 1960s, and the Fed was not able to stem the rise in consumer price growth. Inflation moved from slightly less than 2% YOY at the end of 1965 to 4.7% in late 1968 and further up to 5.9% at the end of 1969. Even as this happened, the FOMC framed its decisions in the shadow of fiscal policy and Treasury financing. The December 1969 transcripts notes that operations were directed at maintaining firm money-market conditions “while taking account of strains in the Treasury bill market,” and repeatedly cites uncertainty about “the extent to which fiscal policy might be relaxed.” Although less explicit than in 1965, these transcripts show that the Fed still weighed government financing needs and fiscal developments heavily in its deliberations, a subtler form of policy coordination that hindered its ability to act independently.

Evidence from the 1970s

Let us fast-forward to the 1970s, when the Board of Governors was led by Chairman Arthur Burns. This period saw even higher inflation and greater volatility in real GDP than the case had been during the late 1960s. Again, the Fed proved highly sensitive to the Administration, persistently adopting policies that complemented rather than constrained government programmes.

As Weise shows in “Political Pressures on Monetary Policy During the US Great Inflation”, Burns in April 1970 warned that if the Fed failed to focus on the unemployment problem, Congress would pass legislation reducing its independence by requiring it to make low-interest housing loans to qualified borrowers: “It would be only a matter of time before the Federal Reserve would find itself in the position of some Latin American central banks.”

The pattern continued in 1971–72. In December 1971 Burns argued that President Nixon’s “New Economic Policy” would stabilise prices and support economic growth. In that context, he said, a Fed policy slowing money growth would invite charges that the Fed was deliberately acting against the government. In January 1972 he stressed that unless the monetary aggregates began to grow faster it would validate the view that the Fed was not “supporting the policies of the Administration and Congress.”

By 1973 staff economist Charles Partee told the Committee that an aggressive anti-inflation policy was “politically unfeasible” and recommended a middle course. In February 1975 Burns opened the meeting by acknowledging “considerable pressure” from Congress, pointing to a resolution instructing the Fed to increase the growth rate of the monetary aggregates. At the same meeting Governor Balles said that a rate cut was dictated by “both the economics of the situation and Congressional concern.”

The tone was similar in 1977. Burns argued that reducing money growth then would be “widely interpreted … as an attempt on the part of the Federal Reserve to frustrate the efforts of a newly elected President.” In July he told his colleagues he could not back lower targets because he had to defend them before Congress and was “concerned about the legislation that we have before the Congress.”

These are just some examples showing how internal discussions and decisions were shaped by political pressure. President Nixon himself captured the mood in 1970: “I respect his independence. However, I hope that independently he will conclude that my views are the ones he should follow.” As Allan Meltzer writes, this was a forecast of the pressure the President and his advisers kept up. And it worked, probably since Burns, like some of his predecessors, aspired to be a key presidential adviser while he was Chairman.

Today’s parallels and market risks

Reading Nixon’s words is striking in the current environment. Today there is mounting pressure from the Administration on the Fed to lower interest rates and accommodate government policy goals. The experience of the 1960s and 1970s shows how dangerous that path can be: it shifts the focus to short-term growth even when inflationary conditions argue for restraint.

The structure of today’s financial system makes the potential consequences even greater. Capital markets are far more open and globally integrated than they were 50 years ago. A Fed perceived as politically compromised would command higher inflation risk premia: investors would demand more compensation to hold US assets, pushing prices down and yields up. Although the US borrows in its own currency, using the Fed’s balance sheet to cap long-term rates would almost certainly intensify downward pressure on the dollar.

Early signs of this dynamic are already visible. Term premiums on longer-dated Treasuries have risen while the dollar has softened. So far the moves have been modest, but they hint at what could happen if the current Administration were to exert more direct or indirect control over the Fed, the very situation Fed officials once lived under and feared would worsen throughout the 1960s and 1970s.

Merk: Å kjøpe og selge aksjer innebærer høy risiko fordi verdien i verdipapirer vil svinge med tilbud og etterspørsel. Historisk avkastning i aksjemarkedet er aldri noen garanti for framtidig avkastning. Framtidig avkastning vil blant annet avhenge av markedsutvikling, aksjeselskapets utvikling, din egen dyktighet, kostnader for kjøp og salg, samt skattemessige forhold.

Innholdet i denne artikkelen er ment verken som investeringsråd eller anbefalinger. Har du noen spørsmål om investeringer, bør du kontakte en finansrådgiver som kjenner deg og din situasjon.