Credit market update:

Tariffs, trade frictions and the end of easy profits

Earnings expectations remain elevated despite clear downside risks.

Earnings expectations remain elevated despite clear downside risks, with markets underestimating both cyclical pressures and the structural shift underway in global trade. If tariffs and broader protectionist measures become a lasting feature of the landscape, equity returns are likely to disappoint, while high-quality credit offers a more stable risk-reward profile.

EPS expectations still too high for a recession scenario

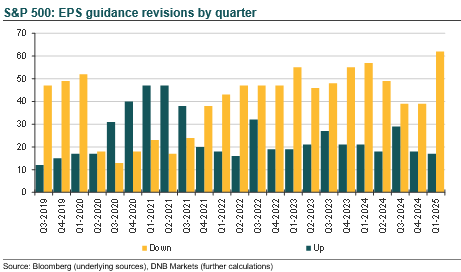

As mentioned in last week’s morning letter, the tariffs introduced by the Trump administration this year are prompting corporates to take a more cautious stance on the near-term outlook. The number of S&P 500 companies issuing negative revisions to their EPS guidance is at a multi-year high.

That is only part of the story. Many firms use guidance tactically to set the stage for a future earnings beat, so some of the current corporate gloom may be strategic. More telling is the growing number of companies withdrawing guidance altogether, a clear signal that the tariffs are having a real impact, especially on those exposed to global value chains.

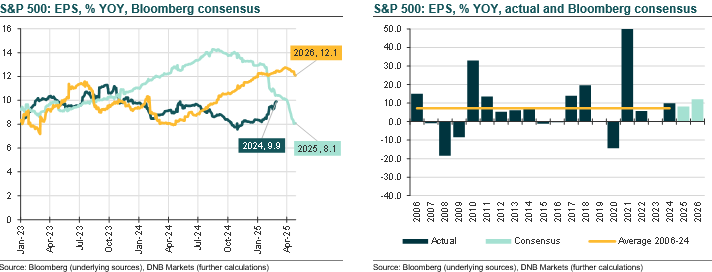

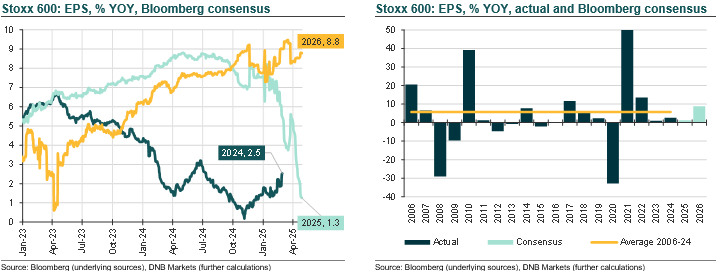

This shift is also visible in analyst forecasts, which have been revised down significantly since the start of the year. Analysts now expect S&P 500 EPS growth of 8.1% YoY in 2025, down from 13% in January. While that’s still above the long-term average of 7.2% (since 2006), it leaves room for further downward revisions if the economy slows more sharply. For context, EPS was flat during the US-China trade war in 2019, fell 1.2% during the oil crisis in 2015, and dropped sharply in both the financial crisis and the Covid shock. 2026 forecasts, currently at 12.1% YoY, also look overly optimistic and are likely to face significant downward revisions.

In Europe, the outlook is more subdued, and here, too, we have seen meaningful downgrades in recent months. After an increase of 2.5% in 2024, analysts began the year forecasting 7.3% EPS growth in 2025. That figure has since dropped to just 1.3%, well below the long-term average of 5.7% and on par with the growth rates seen during the eurozone crisis of 2011–13 and the past two years. As with the S&P 500, both the financial crisis and the Covid shock led to a much more sizeable EPS drop than analysts are expecting.

Taken together, while data for both the S&P 500 and Stoxx 600 already point to a notable deterioration in the business outlook, EPS forecasts are still likely to be revised down significantly if tariffs remain in place. In the US in particular, there is considerable scope for further downgrades, as current growth expectations remain high by historical standards.

Companies increasingly wary of tariffs and economic slowdown risks

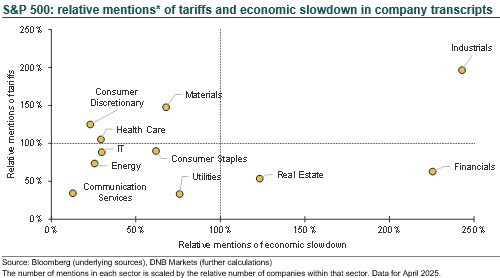

The extent of future EPS downgrades will depend on whether tariffs weigh broadly on economic growth across sectors, or if the impact remains concentrated in a few industries. Transcripts from recent earnings calls suggest that companies across most sectors are highly attentive to the evolving tariff outlook. Firms in industrials, materials, and consumer discretionary appear particularly concerned. Health care, IT, consumer staples, and energy also show elevated sensitivity to tariff risks, while communication services, utilities, real estate, and financials mention the issue less frequently.

Beyond tariff-related uncertainty, there are also signs of growing concern about a broader economic slowdown. Here again, industrials stand out, followed by financials and real estate. In contrast, companies in communication services, utilities, energy, consumer staples, and IT currently appear less concerned so far.

Tariffs a clear negative, says a recent Dallas Fed survey

A key question at this stage is how companies plan to respond to tariffs. Throughout the year, economists have warned that higher import costs would be passed on to consumers, pushing inflation higher. This, in turn, could limit the Fed’s room to ease policy—or at least delay rate cuts—raising downside risks for the broader economy.

A recent Dallas Fed survey sheds light on these dynamics:

Passing on costs is getting harder. Nearly 40% of firms said it had become somewhat or much harder to raise prices compared to three months ago. Just 13% found it easier.

- Tariffs widely seen as a negative. Only 3% said tariffs had a positive impact. A clear majority, 59%, reported a negative impact. The rest were either neutral or uncertain.

- Squeezed margins, weaker sales. While 66% expected higher input costs, only 46% foresaw higher selling prices. As a result, 58% anticipated lower margins, and 41% expected weaker sales.

Cutbacks in employment and capex. 31% expected to reduce employment, 40% planned to cut capex, and 60% had a more negative company outlook overall. - Few are reshoring production. Among firms negatively affected, 55% planned price increases and 44% would absorb costs internally. Only 29% were seeking new domestic suppliers, 15% expected to scale back production or shut down, and just 5% planned to relocate production to the US.

- Most would pass costs to consumers, quickly. Of those increasing prices, 26% expected to pass on the full tariff burden, another 26% most of it, and 41% only part. Over half would raise prices within one month of the tariffs taking effect.

Taken together, the survey suggests that while price pass-through is a likely corporate response, it's not a frictionless process, and many firms face margin pressure and strategic trade-offs in the meantime.

US tariffs challenging the 2000’s profit regime

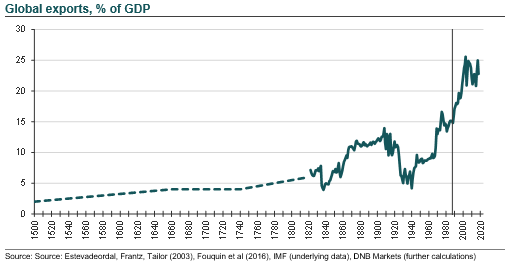

Beyond the short-term earnings pressure, there are deeper structural forces at play. Structurally, tariffs may be part of a new global norm, one defined by very different cross-border frictions than those seen over the past 35 years. The collapse of the Soviet Union in the early 1990s marked the beginning of a new global trading regime, characterised by the steady removal of trade barriers, freer capital flows, and normalised technology transfers, even between countries previously viewed as strategic rivals. When China joined the World Trade Organization in 2001, these dynamics accelerated, enabling the rise of global value chains on a scale unprecedented in economic history.

This period of hyper-globalisation also drove deeper structural changes. In theory, reduced trade barriers fostered greater competition, but primarily at the global level. Within national economies, the opposite often occurred. Globalisation created a winner-takes-all environment, favouring firms with the scale, resources, and reach to build optimised value chains and strategically manage tax liabilities. These firms became so efficient that barriers to entry for newcomers grew significantly.

The US, in particular, has seen a decline in business dynamism. In most sectors, new firm entry and exit rates have fallen sharply, and market concentration has increased. The result is a more entrenched corporate landscape, with less domestic competition and more persistent profitability for incumbents.

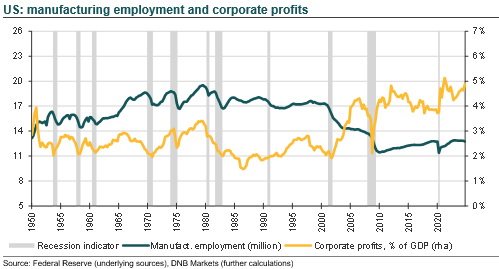

To illustrate the macro impact of these structural changes, consider the chart above, which plots manufacturing employment alongside corporate profits as a share of GDP. From the late 1960s through the late 1990s, US manufacturing employment remained broadly stable at around 17 million jobs. But starting in the early 2000s, job numbers declined sharply, first dropping by about 2 million between 2000 and 2003, then falling further during the financial crisis. Today, there are roughly 13 million manufacturing jobs—a 23% decline from the pre-2000 level.

Over the same period, corporate profits began to rise sharply. From the 1960s to the late 1990s, profits consistently hovered between 2% and 3% of GDP. By 2005, they had jumped to 4%, and in recent years they have climbed further, reaching around 5% of GDP.

This is not to suggest that the decline in manufacturing employment alone explains the rise in corporate profits – the drivers are far more complex. However, the direct effects of globalisation, combined with its role in reducing business dynamism, are among the key contributors. Technological change has also played a role, often reinforcing barriers to entry. Dominant platforms such as Microsoft and Google illustrate how scale and network effects can entrench incumbents and limit competition.

Structural trade-frictions are favourable to bonds

The key point is that Trump’s tariffs, if sustained, are likely to disrupt the very foundation that enabled corporate profits to reach current highs. Trade barriers will raise import costs and, over time, either force a shift toward more costly domestic production or lead to the discontinuation of certain products altogether. The resulting frictions will weigh most heavily on large multinationals, as they have been the primary beneficiaries of the low-friction global trade regime established since the early 1990s.

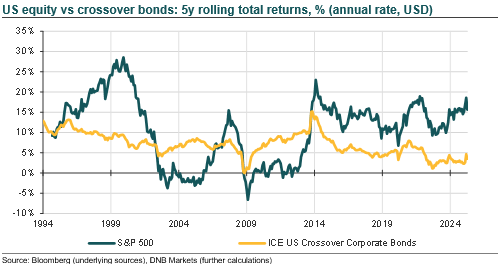

Importantly, while these structural shifts are likely to unfold gradually, they stand in contrast to current equity market valuations, which still imply robust earnings growth in the years ahead. Some analysts are already warning of a decade of low returns in risky assets, and that may prove accurate if Trump’s trade policies become part of a new long-term regime.

In such a scenario, we believe bonds are likely to structurally outperform equities. While short-term equity gains may exceed those from bonds, high equity valuations, slow earnings growth, and structurally higher interest rates all increase the relative attractiveness of bonds over the long run. Meanwhile, the dislocations caused by trade frictions and their near-term drag on growth are likely to favour high-quality credits. These segments offer limited default and refinancing risks, factors that could weigh more heavily on lower-rated issuers (low single-Bs and CCCs) if the environment deteriorates.

Merk: Å kjøpe og selge aksjer innebærer høy risiko fordi verdien i verdipapirer vil svinge med tilbud og etterspørsel. Historisk avkastning i aksjemarkedet er aldri noen garanti for framtidig avkastning. Framtidig avkastning vil blant annet avhenge av markedsutvikling, aksjeselskapets utvikling, din egen dyktighet, kostnader for kjøp og salg, samt skattemessige forhold.

Innholdet i denne artikkelen er ment verken som investeringsråd eller anbefalinger. Har du noen spørsmål om investeringer, bør du kontakte en finansrådgiver som kjenner deg og din situasjon.